Often, choosing not to do something intrusive is the most difficult decision of all

BY DR JONAS FERNANDEZ

PRINCE HAMLET once asked an intriguing question in a play by William Shakespeare. In the opening phrase of the play, Hamlet bemoans the pain and unfairness that life dishes out and contemplates suicide to end the suffering.

But in considering ending it all, he acknowledges the alternative may be worse. Thus, he wondered, “to be or not to be, that is the question”.

Doctors face this dilemma in modern times too. Patients come to us with illnesses and injuries. Life has thrown them a curveball, a spanner into the cogs and everything comes to a screeching halt.

These patients then come looking for help, hoping that a visit to the doctor will turn that frown upside down. Now, these doctors are left with a question to answer, even multiple. That is the question for these modern-day Hamlets – to treat or not to treat.

A single patient may pose multiple questions to the treating doctor. No one is ever the same, so these questions must be peculiar to each patient.

Different types of conditions require different modes of treatment and choosing not to do anything intrusive is the most difficult decision of all. I am often the go-to person among my family and friends for any niggling pain they may have in the joints or the back.

Factors that influence a decision

My go-to response is to leave it alone and rest, as these things are usually self-limiting and will resolve by themselves. It’s not a piece of straightforward advice to accept, though, as not prescribing treatment may not seem like a treatment at all. However, in some instances, the decision to not intervene may be the best one.

Many factors influence the decision on which treatment method to employ. While clinical experience plays an undoubtedly crucial role in the decision-making process, there are often guidelines that can be used.

In some instances, there are scores to be calculated, criteria to be adhered to, and protocols to follow. Taking patients’ symptoms and combining them with investigation results can often yield a particular score, and these scores can then lead to treatment options.

So, the next time you pay a visit to the doctor, and they go quiet all of a sudden and have a blank stare on their faces, you now know that the doctor is processing all the information at their disposal, running it through an algorithm and trying to come up with their best treatment plan.

Let me describe a case that I recently encountered. You could say it was rather humorous (pun intended) in a way.

A 78-year-old lady with an underlying heart condition had a fall. She suffered a fracture of the arm bone (humerus – you get the joke now).

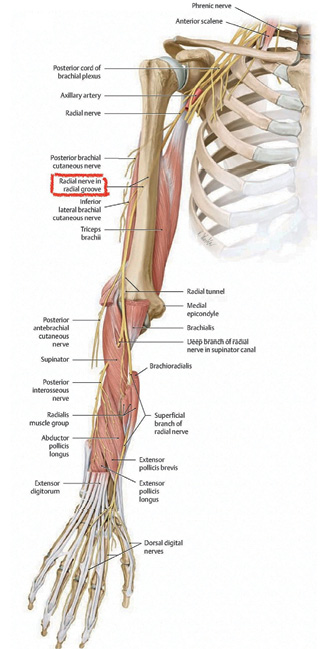

It was complicated with a wrist and finger drop, which is a condition whereby the patient cannot extend the wrist and fingers. This inability to move the hand is caused by nerve damage during the fracture.

The patient had initially visited a private medical centre and was advised to do surgery. However, the patient decided to come to our hospital for the surgery due to certain constraints.

It is when I had my first encounter with her. Much to the patient’s and her family’s despair, I had informed them that she didn’t need the surgery. It was almost as if I had denied her right to proper medical care by not wanting to cut open her arm and stick some metals in there.

Challenges in convincing patients

My first challenge would be to convince them that the other doctor who advised them to have the surgery may have jumped the gun while also trying not to undermine a colleague too much.

My next challenge was to get the patient (and her family) to believe that she could get better without the surgery. I reasoned that the fracture configuration was acceptable and that the inability to move the hand resulted from a nerve injury which had a 90 per cent chance of recovery.

Although doubtful initially, the patient noticed changes with subsequent clinic follow-up. The pain in her arm reduced (indicating the fracture was healing), and she was slowly beginning to move her wrist again (an indication the injured nerve was recovering too).

With time, over a few months, the fracture completely healed, and she gained full mobility of her wrist and fingers. All that while avoiding the risk of surgery, which could have placed her overall well-being at risk given her previous heart condition.

As fresh medical graduates, doctors are required to recite the Hippocratic Oath. The one phrase of the oath that I vividly recall is this: “First, do no harm”.

Modern medicine has significantly improved our living and medical standards. That being said, not every condition requires an aggressive form of intervention. Often, when the situation allows, the conservative path is the better one because, as Hamlet once pondered, the alternative might not be. — The Health

Dr Jonas Fernandez is an Orthopaedic Surgeon at Putrajaya Hospital. He is also a member of the Malaysian Arthroscopy Society (MAS)