Bariatic/metabolic surgery is changing the paradigm of conventional treatment for diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder caused by decreased production or loss in ability to utilise insulin. Insulin is a hormone that helps the body tissues to absorb sugar for energy production.

Diabetes is classified as Type I, Type II and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM). When sugar levels build up in the blood and urine, one may experience symptoms such as frequent urination, increased thirst and appetite.

Obesity and diabetes

At present, diabetes management focuses on maintaining normal blood sugar levels and avoiding too low levels (hypoglycemia). This is achieved by a healthy lifestyle, dietary changes and medications (oral antihyperglycemic agents and insulin).

Diabetic patients are encouraged to lose weight as there is a clear link between weight and diabetes. Weight loss can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes, decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease or result in a partial remission of diabetes.

Studies showed that increase in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes has contributed significantly to the parallel increase in overweight and obesity. The general prevalence of abdominal obesity and diabetes in Type 2 diabetes is inseparable; in particular, the majority of Malaysians with Type 2 diabetes are obese-related. Waist circumference is a risk factor highlighted by the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines of diabetes.

Weight loss and diabetes

Easier said than done! Many diabetics are trying to cut down their weight but to no avail. Bariatric surgery comes to the rescue!

Historically, bariatric surgery was thought to promote weight loss by causing gastric restriction and/or decrease in food absorption. Recently, it was discovered that parts of gut differentially influence glucose control. The advantage of bariatric surgery in patients who also develop Type 2 diabetes has resulted in a shift in the emphasis on weight loss towards enhancing glycemia and other metabolic elements, hence, the term “metabolic surgery”.

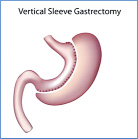

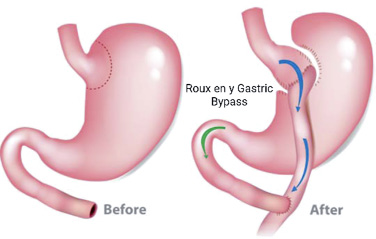

There are various types of metabolic surgery, including laparoscopic adjustable gastric bands, vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and biliopancreatic diversion (BPD). Commonly performed procedures worldwide are the VSG and RYGB.

Diabetes remission rates vary based on the form of procedure, and disease duration. It has repeatedly been shown that most patients retain strong postoperative glycemic regulation despite decreased or no glucose-lowering medication.

How does bariatric/metabolic surgery result in a successful weight loss and remission of diabetes? Unfortunately, the exact mechanisms are still being studied. Bariatric/metabolic surgery causes three phases of anatomical changes:

(i) gastric restriction;

(ii) removal of duodenum and upper intestine;

(iii) quick transfer of food to intestines or small typical channels.

These anatomical improvements cause physiological and molecular changes that aid in the resolution of Type 2 diabetes. These modifications, acting via peripheral and central pathways, would result in decreased liver (hepatic) glucose, increased absorption of tissue glucose, enhanced insulin sensitivity and improved beta-cell activity.

Beta cell and insulin production

Beta cells in the pancreas are responsible for the secretion of insulin. Beta-cell responses resemble two peaks also known as a biphasic pattern. An acute initial peak, representing the first phase insulin secretion happens within the first half hour after a meal.

This is accompanied by a steady rise in insulin secretion, resulting in a smaller volume hump 30–180 minutes after meals. Although the concentration of blood glucose is the major stimulus of fasting insulin secretion, there is an important after meal (postprandial) role for gastrointestinal tract-derived signals, mainly gut hormones released.

This is known as an incretin effect, which makes for an increased secretion of insulin when a glucose load is from the oral route, which may lead to as much as half the insulin secretion following a meal. Two incretin gut hormones, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, are the primary drivers of intestinal nutrient-induced insulin secretion (GIP).

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy which reduced the volume of the stomach.

Roux en Y Gastric Bypass which bypasses the stomach to the jejunum.

In the case of Type 2 diabetes, it is the result of the gradual failure of pancreatic beta-cell function with increasing insulin resistance. Once the pancreas is unable to compensate for insulin resistance, an increase in blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia) develops, leading to the acceleration of beta-cell deterioration characterised by the loss of sensitivity and an impaired insulin secretion.

Metabolic surgery partly restores the dysfunction of the ß-cell. The enhanced GLP-1 secretion is assumed to be a significant weight loss independent factor that leads to the postoperative change after metabolic surgery.

Insulin sensitivity

After a meal, insulin release firstly suppresses liver glucose production and allowing glucose uptake into our tissues.

In insulin resistance, higher levels of insulin required to compensate for hyperglycemia. Following metabolic surgery, there is a marked improvement in insulin sensitivity that differs depending on the timing: early versus late postoperative period.

This early progress is secondary to a rise in liver insulin sensitivity as demonstrated by a decline in the body’s glucose production. Peripheral insulin sensitivity, including skeletal muscle and fat tissue, does not alter during the early postoperative cycle, but increases steadily afterwards and has a near association with weight loss. In the late postoperative cycle (three to six months after surgery), weight loss plays an important in additional insulin sensitivity.

Glucose absorption

After metabolic surgery, there are changes in the glucose metabolism within the gut. A lower glucose absorption has been shown to happen in RYGB and VSG, although, the mechanisms are different.

After RYGB, undigested nutrients encounter bile acids and other digestive secretions that facilitate the absorption of nutrients. Glucose absorption is dampened in the alimentary limb and rises in the common limb secondary to altered bile acid flow.

Intestinal glucose is consumed by the apical sodium glucose co-transporter 1 (SGLT1), which absorbs sodium and glucose together from the intestinal lumen. Sodium is derived from bile and other digestive fluids.

There is a transition in bile acid trafficking not being exposed to these digestive fluids without the involvement of sodium being co-transported with glucose. In fact, despite SGLT1 expression or function being preserved, bile acids exclusion itself reduces the intestinal sodium-glucose absorption.

Bile acids attenuate the intestinal trafficking of sodium by decreasing the sodium content of the intestine. The inhibition of SGLT1 results in a reduction in postprandial glucose concentrations and improvements in sugar control.

In addition to this, post-RYGB surgery, there is increase in gut mucosa cells caused by sensitivity of the mucosa to undigested nutrients. There is emerging evidence that this causes a reprogramming of glucose metabolism and raises the metabolic rate to satisfy higher energy demand, improving carbohydrate intake.

This improves intestinal glucose utilization, secondary to improved intestinal expression of GLUT1 after RYGB, regardless of weight loss or increases in insulin secretion and sensitivity.

After metabolic surgery, all these outcomes put the gut within the group of organs/peripheral tissues responsible for increasing glucose disposal. With regard to VSG glucose absorption in the small intestine is reduced since part of the stomach is removed. Therefore, leptin- and ghrelin-expressing cells are reduced.

Ghrelin raises appetite, decreases gastric emptying, controls energy intake and reduces glucose-induced insulin release and sensitivity. Gastric leptin is generated in the stomach and secreted to the small intestine, where it is assumed to stimulate glucose absorption by enhancing the glucose transporter-2 (GLUT2) in the jejunum.

It has been postulated that after VSG, ghrelin and leptin depletion is one of the main factors contributing to the improvement in glucose homeostasis.

Three laparoscopic ports inserted for bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery performed laparoscopically by lead surgeon Dr Nik Ritza.

Laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive with little scaring post procedure.

Glucose screening

The release of glucose from the small intestine is activated by two main glucose producing enzymes: glucose-6-phosphatase (Glc6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK).

Newly synthesized glucose is detected by the hepato-portal or liver glucose sensing mechanism, modulating the production of liver glucose. This involves glucose transporter (GLUT-2) and is potentiated by GLP-1. The liver glucose-appearance sensing suppresses liver glucose production but increases peripheral tissue glucose uptake.

In addition, liver glucose sensing causes a decrease in food consumption. These metabolic effects created by the liver nervous system seem to connect to the central control of hormones ie the hypothalamus. Following RYGB surgery, the PEPCK and Glc6Pase enzymes in the intestines have improved expression and activities. This results in increased intestinal glucose release to the liver that in turn suppresses the liver production of glucose and food intake.

Increased intestinal glucose production and activation of the liver glucose sensor through the GLUT-2-dependent pathway is postulated for which RYGB increases insulin sensitivity and decreases the consumption of food.

Fat tissue

Excess of fat or adipose tissue, specifically its central deposition of the abdomen, decreases insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function. It is an independent risk factor for Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fat is a hormonal organ that releases various hormones, cytokines and molecules that not only affect body weight, food consumption and energy balance, but also controls glucose and lipid metabolism. In the case of cytokines, excess fat deposition is characterized by long term low-grade inflammation implicated in T2DM.

As mentioned above, major weight loss occurs after metabolic surgery. It makes sense to lose both fat mass and fat-free mass as seen in traditional diets. However, following surgical-induced weight loss, the body’s structure improves with a lowered body fat content as well as a modest decline in fat-free mass.

In comparison, not only is there a net body fat reduction, but fat surrounding organs and muscles are also reduced. This metabolically advantageous redistribution of fat further adds to the increase in glucose metabolism shown following surgical-induced weight loss: there is an improvement in liver insulin sensitivity owing to reduced fat in surrounding organs, decreased muscle mass loss that improved muscle glucose absorption.

The fat tissue itself undergoes a variety of changes in secretory profile, structure, glucose, and lipid metabolism. Both findings confirm the function of adipose tissue as one of the contributors to glycemic recovery observed after metabolic surgery.

Conclusion

Bariatric/metabolic surgery is effective and has a relatively low risk, leading to its acceptance within the algorithm in managing diabetes mellitus. The question of whether it will become a mainstream treatment that most diabetic patients would accept is still at stake.

The advantages of surgery are more perceptible if being done during the early stages rather than waiting for irreversible diabetic complications. Therefore, an honest discussion with the endocrinologist and bariatric/metabolic surgeon is essential for optimum treatment and management of obesity and/or diabetes mellitus. — The Health

Dr Nik Ritza is Professor in Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Consultant General Surgeon, Department of Surgery, UKM Medical Centre (UKMMC), Dr Hardip is Lecturer and Specialist Otorhinolaryngologist, Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, UKMMC and Dr Mardiana is House Officer, Department of Surgery, UKMMC.

The fat tissue itself undergoes a variety of changes in secretory profile, structure, glucose, and lipid metabolism. Both findings confirm the function of adipose tissue as one of the contributors to glycemic recovery observed after metabolic surgery.

Dangers of diabetes

An estimated 463 million people have diabetes worldwide. Type 2 diabetes constitutes 90 per cent of the cases in 2019 with similar rates between male and female. It is likely to continue to rise.

Malaysia is no exception with a significant increase in Type 2 diabetes among adults aged 30 years. This should not be ignored as diabetes mellitus is closely related to small and large vessel complications, as well as premature mortality.

If untreated, one is susceptible to acute complications including diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state and even death. Small vessel (affecting the eye, kidneys and nerves) and large vessel complications (angina, heart attack and stroke) has been seen in patients with long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Cost of diabetes

Diabetics require ongoing treatment to manage and keep their condition stable for the long run. This in turn increases healthcare expenditure.

According to the Pharmaceutical Services Division of the Ministry of Health (MoH) Malaysia, the cost of a diabetic patient was estimated to be RM466.20 over six months in 2014. That amount is bound to be higher today!

However, the figure excludes treatment for long term complications such as stroke, heart disease and kidney disease. Kidney dialysis costs between RM150 and RM300 per session, while a heart transplant may cost up to RM100,000.

Diabetes certainly burns a hole in one’s pocket!