Use of fossil fuel for electric power generation and transport are the ‘worst offenders’ for carbon emissions

LAL’S CHAT

The Covid-19 pandemic impacted so many aspects of life that it seems to be creating a whole new world on this planet.

Although its impact on the global society and economy has been mainly negative, it has also encouraged positive results. Air and water pollution is reduced mostly by reducing anthropogenic activities, which have been heavily dependent on the combustion of fossil fuels that spew global warming (or carbon) emissions into the atmosphere.

Use of fossil fuel for electric power generation and transport are the “worst offenders” for these emissions. Even before the pandemic, the global community had reduced fossil fuels, particularly coal and oil, for power generation, transport and other industrial services.

Thus, most initiatives to reduce carbon emissions have been directed at decommissioning the older coal-fired power plants and stopping the continued development of coal-fired power plants, including the so-called clean(er) coal ultra-supercritical power plants.

Malaysia too (at least TNB) has committed to not developing more coal-fired power plants beyond 2030.

The next most apparent “culprit” of carbon emissions is the transport sector. This sector is based on internal combustion engine (ICE) power systems using liquid fossil fuels such as petrol and diesel (including bio-fuels) and moving towards NG (natural gas), CNG (compressed natural gas), biogas, and hydrogen for use as gas or with fuel cells to generate electricity.

Rail transport has long been mostly electrified globally as being the most convenient and cost-effective form of motive power for such systems. Even urban road transport was electrified in the past with electric trams and buses. However, these forms of urban transport lost their advantage over time for various reasons.

However, the introduction of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) from the 1990s, BEVs (battery electric vehicles) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) promises the most drastic paradigm shift for motorised road transport to reduce carbon emissions from this sector.

This is helped further by the proliferation of EEVs (energy-efficient vehicles) that promises reduced emissions through the design of higher efficiency ICE engines.

Electric motor power systems and drive trains are indisputably more efficient than the ICE and hybrid vehicles as they have fewer moving parts that reduce friction losses and not have to dissipate unused thermal energy that fuel combustion produces.

Moreover, they also need much less supplementary oil use such as for lubrication and cooling.

Consequently, the world has seen the explosive promotion of “battery electric vehicles (BEVs)” this century, especially with Elon Musk’s iconic Tesla brand.

Most mainstream and new entrants in the automotive sector, anticipating an EV boom, have jumped on the bandwagon to produce BEVs.

Notwithstanding the high-profile promotion of EVs and the double-digit growth rates of their production volume and sales, they still form a small portion (estimated to be only about one per cent) of the global road vehicle population.

Nevertheless, EVs and HFCVs are seen as an essential tool to help reduce global warming emissions from the road transport sector.

An important point to note is the definition of “EVs”, as some reports include HEVs (whether the mild hybrids or PHEVs) which supplement their energy use with battery recharging using the grid-supplied electricity from the power plants that feed the grid. So, are such “EVs” really low-carbon emission vehicles?

The electricity used to recharge the batteries for EVs & PHEVs in most countries is predominantly from fossil fuels. However, some countries like Costa Rica, Iceland, and Norway produce virtually 100 per cent of their electricity from RE sources.

While nuclear-powered electricity generation qualifies as low carbon emission, it is not universally accepted due to its perceived radioactive related hazards.

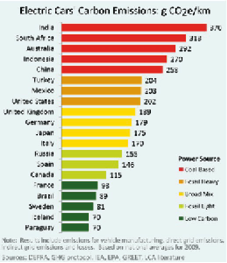

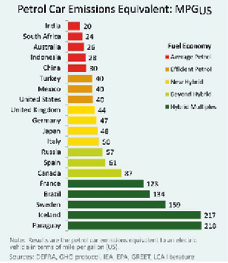

The charts (Fig 1) show a comparison of the carbon emissions from conventional ICE vehicles and EVs, under different power generation systems and the ICE efficiency grades.

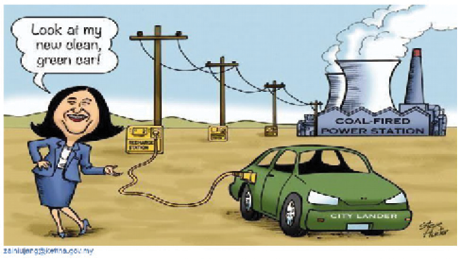

So, are EVs really “clean”? Let us look at some issues of BEVs, as indicated in the reports below (Fig 2).

A healthy urban environment

We have to consider the different power generating systems’ primary energy mix in comparing the comparative emissions from ICE, HEV, BEV and HFCV powered road transport vehicles to assess their contribution to carbon emission reduction endeavours.

The issue of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is still in its infancy but could be significant in the future.

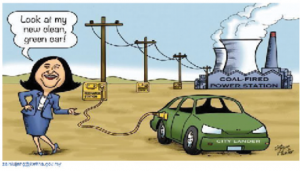

It was ironic that a former Chief Secretary of KeTTHA (Ministry of Energy, Green Technology and Water) included this slide (Fig 3) in his presentation on Planning for Sustainable Energy to UTM on May 17, 2017.

Sarawak exploits hydrogen (using low-cost hydroelectric energy to generate hydrogen through electrolysis) for its experimental hydrogen fuel cell buses and a planned LRT system.

Notwithstanding the content above, which appears to be against over-hyped promotion of EVs in Malaysia, electric mobility for public transport such as MRT, LRT, Monorail & electric buses (BEV) for intra urban public transport (as BRT, bus rapid transit) deserve strong support due to their zero tailpipe emissions, even if they may be less cost-effective than fossil-fuelled buses such as diesel (including bio-diesel) and CNG.

Polluting emission reduction in urban areas is an important civil desire for a healthy urban environment.

Malaysians must surely be aware of the clean air, especially in the Klang Valley during the long holidays (pre-Covid 19), when a large portion of the Klang Valley residents “balik kampong”. That eliminated the heavy vehicle emissions during the week-long holidays.

Realistically, extensive use of EVs and PHEVs is not the only cost-effective avenue for Malaysia, and the global community to reduce carbon emissions from the transport infrastructure.

HEVs, especially those without “plug-in-charging”, and EEVs may be the most cost-effective options to reduce carbon emissions from the motorised road transport sector. — @green

Comparing Electric Emissions to Petrol Cars

Electric car’s emissions can vary from similar to average petrol cars to less than half those of the best petrol hybrids.

We show this by accounting for the difference in vehicle manufacturing emissions and then calculating the equivalent petrol vehicle emssions in terms fuel economy, MPGUS. Presented in this way the results more intuitive, allowing us to compare electric car emissions with conventional vehicles in a more familiar metric.

Figure 1

Figure 2

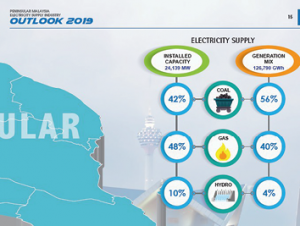

Malaysia is in the complex

position of having predominantly fossil-fuelled power generation (around 96 per cent in 2019 as shown in the Suruhanjaya Tenaga Outlook 2019 extract) in the peninsula where the promotion of EVs is most prevalent, while Sarawak has the largest share of non-fossil fuel power generation due to its vast large hydroelectric power plants in operation and under construction or planned for construction.

Figure 3