Understanding how our bones change

BY DR JONAS FERNANDEZ

No, it is not the one that howls at the sight of the full moon. What I am referring to is no animal. Instead, it’s German anatomist and surgeon Julian Wolff.

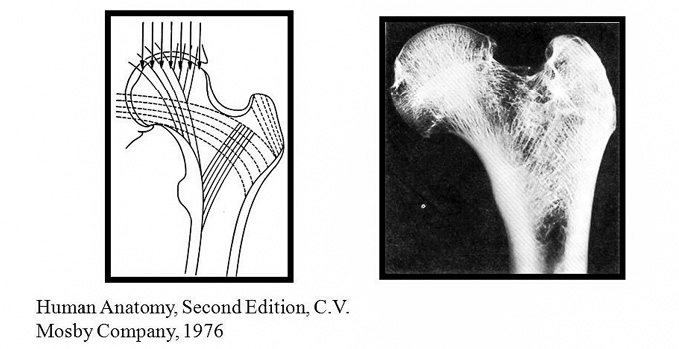

Wolff’s idea at that time, which still holds, is that naturally healthy bones will adapt and change to the stress it is subjected to.

It’s fascinating how much our bones can change, whether for the good or otherwise. In medical terms, this ability to “shape back to its original self” is termed “remodelling”.

Although the adult or mature bone poses this ability to a certain degree, it is in children that it is most pronounced.

Before we go further into how that happens, let us first consider what makes a child’s bone more impressive. A child isn’t born with all its bones fully formed. Instead, they have what we coin as primary and secondary ossification centres.

Before we go further into how that happens, let us first consider what makes a child’s bone more impressive. A child isn’t born with all its bones fully formed. Instead, they have what we coin as primary and secondary ossification centres.

What this simply means is that newborn children develop adult-like bones as they grow older. One fascinating example is the patella bone. The next time you visit your newborn nephew or niece, have a feel at their knees. You would not be able to feel the “knee cap”.

Fractures involving children

In addition to forming new bones, immature bones also have what we call “physis”, or the growth plate. The physis is often referred to as the factory of the bone. They’re found at the ends of long bones like the femur (thigh) and humerus (arm).

When looked at under a microscope, they can be divided into a few distinct zones, each playing an essential role in normal growth. Short stature or dwarfism occurs when there’s a congenital disability involving the physis.

Because of how different the skeleton of a child is, fractures involving them also tend to be different to those of adults. They tend to have more incomplete fractures, meaning that the fracture isn’t through and through.

This happens as their bones tend to be more plastic. As such, their bones will tend to bend and deform more before breaking. These incomplete fractures are called “greenstick” or “torus” fractures. The other type of fracture unique to children involves the growth plate.

So where does Wolff’s Law come into all of these? As mentioned in my earlier column titled “To Be or Not to Be”, there are guidelines to follow in terms of just how much deformity a fractured bone can be left to heal by itself before surgical intervention becomes necessary.

It is also true in children, except that one can accept a lot more deformities in kids.

Keep healthy and develop solid bones

Why is this? It is because of the body’s extraordinary ability to not only heal itself but also, to reshape the bone back to its original form. It is especially true in children who have the most growth years left ahead of them.

This means the younger one is, the better the potential for the body to remodel a bone that has been left deformed by a fracture.

Apart from age, other factors that play a role include the distance of the fracture to the growth plate and the direction of the deformity. For the distance of the fracture to the

growth plate, the closer the fracture to the growth plate, the better the outcome.

As for the direction of the deformity, better remodelling is seen if the direction of the deformation is in the same plane as the adjacent joint.

Lastly, fractures involving the growth plate might have their worst prognosis as the trauma might have caused permanent damage to the “bone factory”.

It truly is fantastic that our body can reshape itself just from the stresses applied to it. The remodelling of fractured bones is just one way Wolff’s Law applies.

Bones also get more robust when stresses like exercise act on it. So there you have it, prevention is better than cure. Let’s start by keeping healthy and developing solid bones.

And if it fractures, then let nature take its course and allow it to remodel back. – The Health

Dr Jonas Fernandez is an Orthopaedic Surgeon at Putrajaya Hospital. He is also a member of the Malaysian Arthroscopy Society (MAS).