Rates of this blood cancer have jumped but today, life expectancy has at least doubled in some cases, thanks to increased research, new learnings and innovative advances

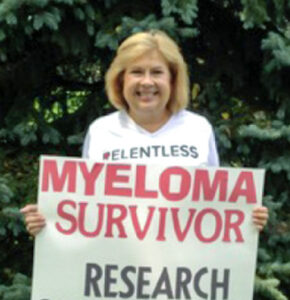

Cindy Chmielewski had never heard of multiple myeloma until the day her doctor informed her that she had it.

She recalls telling others about her diagnosis and having to correct them when they misunderstood and thought she had melanoma, a form of skin cancer, rather than myeloma, a type of blood cancer.

Prior to her diagnosis, Chmielewski spent two years seeing an orthopaedic surgeon for severe back pain. The doctor insisted that she had degenerative disc disease, a common cause of back pain.

But that wasn’t what was wrong with Chmielewski, and pain medication and physical therapy weren’t helping. Finally, the pain got so severe that she went back to the doctor in tears.

“I was a fifth-grade teacher at the time, yet I couldn’t stand up long enough to be the playground monitor. I couldn’t take kids on field trips because the bumpy bus ride would be too painful,” she says.

The doctor finally sent her for X-rays, which revealed numerous compression fractures in her back. Chmielewski was getting ready to undergo surgery to stabilise her spine when preop blood work came back “totally abnormal.” She was quickly referred to a haematologist, who diagnosed her with multiple myeloma.

In the 14 years since, Chmielewski, now in remission, has made it her mission to educate herself, as well as the public, about the disease. She’s become an outspoken patient advocate who posts extensively on Twitter, speaks at medical conferences and shares her experience with pharmaceutical companies that are seeking patient input, including the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson.

Johnson & Johnson has been dedicated to developing innovative treatments for multiple myeloma for nearly 20 years and is committed to working toward its goal of one day eliminating the disease.

Here are five things we now understand about this cancer, including what advances may lie on the horizon.

1. Multiple myeloma may not cause any noticeable symptoms until the disease is advanced

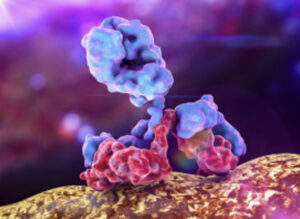

Multiple myeloma typically starts in the bone marrow, which is the birthplace of new blood cells and specifically is impacted by antibody-producing white blood cells known as plasma cells. (“Multiple myeloma” and “myeloma” can be used interchangeably; “multiple” refers to the fact that the cancer often grows in multiple areas of the marrow.)

In healthy people, plasma cells make antibodies to multiple targets, protecting patients against all types of infections. In patients with multiple myeloma, however, plasma cells grow abnormally in an uncontrolled fashion, rendering the cells cancerous.

As these harmful cells build up in the bone marrow and often make an abnormal antibody called an M protein, there’s less room for healthy blood cells to grow. The result? A potential lack of adequate red blood cells, platelets and other types of white blood cells needed to successfully fight off infections.

These issues often lead to the presence of clinical disease features and symptoms, known as CRAB criteria, explains Jordan Schecter, M.D., Vice President, Cellular Therapy at Janssen.

CRAB stands for high Calcium levels (which rise in the blood as bone is broken down), Renal failure (the M protein secreted by the cancerous plasma cells causes kidney damage), Anemia (due to lack of red blood cells) and Bone lesions (fractures are common due to breakdown of bone, often in the spine or ribs).

While bone pain, fatigue and weakness can be tipoffs, many people with multiple myeloma don’t have any noticeable symptoms until the disease has advanced. When this cancer is detected early, it’s usually thanks to routine blood tests finding high protein levels in the blood, due to the abnormal M protein.

2. The disease is relatively rare, but it’s becoming more common

Nearly 35,000 adults in the US are diagnosed with myeloma each year. That makes it a relatively rare cancer compared to breast cancer (about 264,000 cases each year) or lung cancer (about 240,000 per year), but it’s hardly an insignificant number. Also noteworthy is the fact that myeloma is on the rise. Worldwide, incidence jumped 126 per cent between 1990 and 2016.

This trend might be explained by the fact that people are living longer, because the risk of myeloma increases with age and is most often diagnosed in people over age 60. It’s also more prevalent in black people than it is in white people, and it’s slightly more common in men than it is in women. Of course, not everyone who gets the disease fits the mould: Chmielewski, a white woman, was diagnosed in her 40s.

3. It is possible to have a precursor condition that might not require treatment.

Some people, like Chmielewski, are diagnosed with full-blown myeloma that meets the CRAB criteria. But because the disease may be preceded by two precursor states, others may learn at an earlier stage—usually through routine bloodwork, since these precursor stages aren’t accompanied by symptoms.

The earlier precursor state is MGUS, which stands for Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. Only one per cent progress to multiple myeloma. “Most of them can be closely monitored and will hopefully never need treatment,” says Dr Schecter.

The other precursor state, called smoldering multiple myeloma, is more of a middle ground, he explains. “It’s an asymptomatic form of myeloma that doesn’t meet the CRAB criteria, and the standard of care is to not treat those patients but rather just closely monitor them.” However, about 15 per cent of people with smouldering multiple myeloma will progress to multiple myeloma within three years.

For that reason, scientists are working to identify who is at highest risk of progressing. Clinical trials designed to find out which smouldering multiple myeloma patients may benefit from earlier treatment are currently underway. “The standard of care is evolving,” says Dr Schecter.

4. Multiple myeloma is rarely treated with surgery, and drug regimens are often adjusted

Because multiple myeloma is a blood cancer rather than a solid tumor, it’s rarely treated with surgery. Instead, patients receive induction therapy comprised of medications administered both orally and subcutaneously (under the skin), which are designed to induce remission.

The current mainstays of treatment come from three main classes of drugs, explains Dr Schecter: IMiDs, or immunomodulatory drugs, which have direct activity against the plasma cells and also harness the power of the body’s immune system; proteasome inhibitors, which can help kill myeloma cells; and CD38 antibodies, which bind to a protein on myeloma cells.

This induction therapy is often followed by an autologous stem cell transplant—a procedure in which the patient’s own bone marrow stem cells are removed from the blood and infused after a high dose of chemotherapy is used to kill off cancerous stem cells in the bone marrow. However, many patients are too old or frail to undergo a stem cell transplant.

When stem cell transplants fail or the disease progresses despite a transplant, oncologists generally turn back to drugs in these three classes, using either different drugs or combinations, as patients will need to change their drugs or regimen if their current one stops working. However, patients typically are not cured and relapse—pointing to the need for more therapeutic options.

5. There’s no cure for the large majority of patients, but people now have more treatment options – and hope

When Chmielewski was first diagnosed, there were only a few myeloma drugs on the market. Fortunately, these treatments did put her into long-term remission. “If those had stopped working for me, there would have been nothing else available” outside of a clinical trial, she says.

Now, when someone relapses, there are multiple combinations of approved drugs that patients could try, some of which Janssen has developed, says Blake Bartlett, Ph.D., head of Multiple Myeloma & Plasma Cell Disorders, Global Medical Affairs, Janssen. The current options include drugs with a variety of mechanisms of action in at least five separate drug classes.

As myeloma treatments are advancing, people have more hope in managing the disease. “About 20 years ago, the life expectancy was about three years, and overall, now it is at least five to six years,” says Bartlett.

Although long-term data on the latest therapies and updated drug regimens is not yet available, patients with standard risk features who incorporate newer options, including some of the latest immunotherapies, may now expect to live more than five or six years with the disease, he adds.

“My daughter was 19 when I was diagnosed, and now we’re going dress shopping for her wedding next year,” says Chmielewski. “When I was newly diagnosed, I never thought I’d be around to see her get married.” She is still faring well on older drugs she’s been taking for many years, but knowing that other options are out there “gives me so much hope, because I don’t have to worry as much if I relapse someday.”

“My daughter was 19 when I was diagnosed, and now we’re going dress shopping for her wedding next year,” says Chmielewski. “When I was newly diagnosed, I never thought I’d be around to see her get married.” She is still faring well on older drugs she’s been taking for many years, but knowing that other options are out there “gives me so much hope, because I don’t have to worry as much if I relapse someday.”

As research in this area continues to advance, so does hope. A potential cure might even be on the horizon, perhaps by treating patients earlier with different combinations or sequences of existing or developing therapies that are being investigated in clinical trials.

“We’re focused on developing first-in-class or best-in class therapies and really aim to change the treatment landscape,” says Bartlett. “We’re also conducting clinical studies to determine the best way to integrate our new generation of therapies into the standard of care, which might someday help us deliver cures for most patients.” – The Health

This article appeared recently on the website of Johnson & Johnson