In his pursuit to improve strawberry birthmark treatment, Dr Swee Tan discovered potential effective and affordable cancer treatment

BY KHIRTINI K KUMARAN

DISSATISFIED with the conventional treatment for infantile haemangioma, also known as a strawberry birthmark, Dr Swee Tan began his research to better understand the condition in search of better treatment to improve the patients’ quality of life.

Dr Tan is the Founder and Executive Director of the Gillies McIndoe Research Institute (GMRI); and Consultant Plastic Surgeon at Hutt Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand.

Born to a poor family of 14 children in Senggarang, Batu Pahat, Johor, he aspired to become a doctor. He enrolled in the medical school at Melbourne University, Australia, in 1980 and later trained as a plastic surgeon in New Zealand.

As a plastic surgeon, Dr Tan managed patients with disfiguring and life-threatening conditions and finds many existing treatments are unsatisfactory, invasive, and costly.

“I believe we need to go to the lab and try to better understand these conditions, which will allow us to design an effective, inexpensive and convenient treatment for patients.

So in 1996, he enrolled in a part-time PhD programme at the University of Otago to better understand strawberry birthmarks and develop a better way to treat the problem.

Improving strawberry birthmark treatment

A strawberry birthmark consists of a clump of tiny blood vessels that form under the skin. It causes a raised red skin growth that is usually present within 2-3 weeks after birth. It is a benign (non-cancerous) tumour.

They usually grow rapidly for a few months, stabilise in size, and then gradually subside over a few years, often leaving a fatty lump or skin blemish. However, the location and size of the growth may affect bodily functions such as impairing eyesight or blocking airways. It also significantly affects one’s appearance and self-esteem.

For such cases, traditional treatments involved initial high-dose steroids and sometimes chemotherapy, often followed by surgery and/or laser therapy, which Dr Tan believes are too harsh on the children.

“After 15 years of work, we found that strawberry birthmark is caused by stem cells with evidence that they originate from the placenta. We discovered the involvement of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), a regulatory system known to control blood pressure.

“These discoveries underscore the way we treat strawberry birthmarks now, using blood pressure-lowering drugs that make strawberry birthmarks shrink and disappear.

“The RAS consists of many steps, and we have existing medications that can be used to block each of the steps. For example, we can use beta-blockers to block the system to treat strawberry birthmarks.

“Propranolol, a beta-blocker, is now the treatment of choice for strawberry birthmark since 2009. It is a simple and cost-effective treatment, taken orally, and the patient is not required to be in the hospital.

As the RAS can be blocked with other medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, Dr Tan and his team conducted a clinical trial using the ACE inhibitor Captopril to treat strawberry birthmarks, at Hutt Hospital.

“This was the world’s first-ever clinical trial using this approach to treat a tumour.”

Drug repurposing for cancer treatment

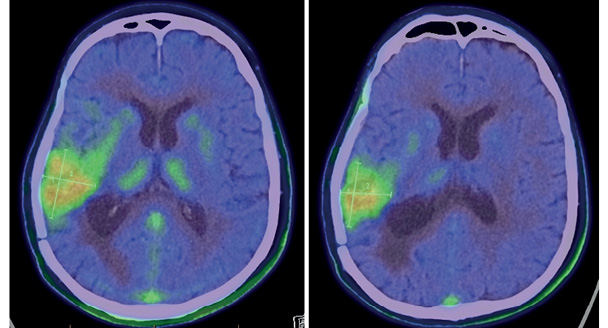

Based on the research breakthrough with strawberry birthmarks, Dr Tan and his team researched cancer stem cells, the proposed origin of cancer, and found that the RAS is expressed by cancer stem cells in 14 cancer types, including brain, skin, colon, and lung cancers.

“Cancer stem cells are highly tumorigenic and possess self-renewal properties, which is why cancer can recur and spread, forming new tumours, and resists conventional treatment,” he explained.

“So, this potentially allows us to intervene and control the cancer stem cells by blocking various steps of the RAS by repurposing well-established drugs.”

Glioblastoma, the most common and most aggressive form of brain tumour, was one of the first cancers Dr Tan and his team investigated. They have now designed a phase II clinical trial for glioblastoma patients.

Drug repurposing, said Dr Tan, is hugely less expensive than developing a novel drug and takes less time to reach the market.

He, however, noted as there are no commercial incentives, the GMRI relies on philanthropy to support their drug repurposing research.

Dr Tan’s team has received regulatory approvals to proceed with the phase II glioblastoma clinical trial and they are actively seeking philanthropic donations it get off the ground.

GMRI’s research focus

While working on his PhD, Dr Tan decided to establish a research institute, and the GMRI was officially opened at the end of 2013 by former New Zealand Prime Minister Sir John Key.

The GMRI’s research focuses on the role of stem cells in diseases such as cancer, fibrotic conditions, vascular birthmarks, and regenerative medicine.

“We are also working on organoid systems by creating a microscopic organs in the lab that allows you to investigate certain conditions and test drugs with different concentrations and combinations. So, we are developing organoid systems for glioblastoma, colon cancer and lung cancer.

“It’s an exciting area of work that we’re doing. It will give us a platform to investigate these conditions. And of course, the knowledge can be applied to developing other organoids.”

As for the future of managing haemangiomas, he believes in continued research and hopes to improve and refine treatment for strawberry birthmarks and the other types of vascular birthmarks.

The GMRI is a non-profit organisation supported almost exclusively by philanthropic donations. Dr Tan shared the pandemic had affected their funding because governments and people worldwide were focused on Covid-19.

“Reduced funding and lockdowns have undermined our ability to make progress on time. Everything was hard.”

Despite the challenges, Dr Tan is pleased to continue his work and humbled by the contributions and participation of those eager to help humankind. — The Health