The 26th Conference of Parties (COP) 26, in Glasgow, Scotland, was stated to be “The last best chance” for the global community to make the necessary enhanced commitments to realise the objective of limiting the global temperature rise due to climate change to “below 20C, and preferably to 1.50C”, by the end of this century.

It was agreed upon under The Paris Agreement (PA) in 2015. COP27 was in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, on Nov 6-18, 2022.

What happened in the year that has gone by so quickly? The hopes that blossomed after COP 26 appear to have evaporated during the past year, with fossil fuel power generation (including coal) gaining greater traction.

This has happened in no small measure due to the resurgent global economic activity after the constraints due to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions were gradually removed worldwide. The unfortunate war in Ukraine and its impact on gas supply disruptions, especially in Europe, have not helped either.

COP26 raised great hopes for all nations to aim for Net Zero Emissions (NZE) by the middle of this century to limit the global temperature rise to below 2oC, and preferably to only 1.5oC, as agreed at COP 21 in 2015 (Paris Agreement) to ensure a liveable planet for all forms of life.

This included the need to reduce global GHG emissions by about 50 per cent from the 2005 levels by 2030 to achieve the target. This target seems out of reach for most countries committed to it at Glasgow in 2021.

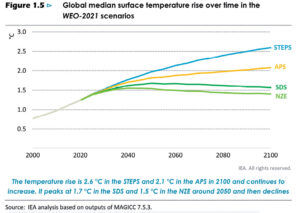

The charts below from IEA World Energy Outlook – 2021 projections show the limits of “emission targets” needed to constrain the global temperature rise to 1.5oC under different emission reduction policy scenarios.

These figures present rather tough challenges for the global community to meet, mainly to satisfy the mid-term target of 50 per cent emission reduction from the 2005 levels by 2030.

As things stand now, these ambitious targets look out of reach unless drastic policy commitments were realised at COP27.

Where does Malaysia stand in these ‘climate emergency’ conditions?

Malaysia committed under the NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution 2021) to reduce the national carbon intensity to GDP by 45 per cent by 2030 from its value in 2005. Malaysia had indicated it had achieved about 33 per cent carbon intensity to GDP by 2015, so any commitment to reach a 45 per cent carbon intensity by 2030 seems relatively insignificant (not at all challenging).

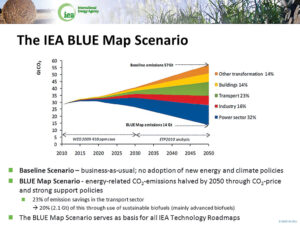

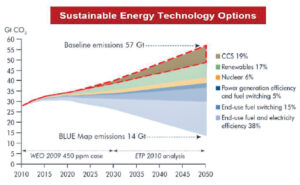

The IEA Blue Map scenario shows that EE, or efficient use of energy, provides the “biggest bang for the buck” for efforts to reduce carbon emissions, comprising about 38 per cent of the desired reductions. CCUS, with a 19 per cent share and renewables, with a 17 per cent share, are the next most prominent components. CCUS is not quite mainstream yet. So, using renewable energy (RE) resources is the best bet for Malaysia to achieve its carbon intensity reduction aspirations.

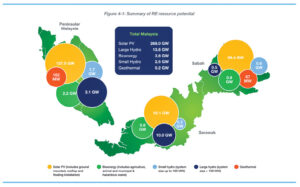

While there are many forms of RE globally, Malaysia has a relatively limited range of viable RE resources to exploit. These include solar PV, hydroelectric power, biomass and biogas, and biofuels. Other high-capacity resources such as geothermal, wind and marine REs such as tidal, wave and OTEC (Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion) are either inadequate for commercial exploitation or not economically practical yet.

The excerpt below from SEDA’s MyRER shows the current status of the RE resources in operation in Malaysia, where large hydropower dominates.

It says: As of 2020, RE installed capacity in Malaysia amounted to 8,450 MW. Large hydro is the largest contributor to RE capacity with 5,692 MW, followed by solar PV and biomass with 1,534 MW and 594 MW, respectively. Small hydro capacity amounts to 507 MW and biogas to 123 MW.

MyRER also shows, in the Figure 0-6, the tremendous potential RE capacity technically available for Malaysia to exploit and how much of it is likely to be utilised by 2025 and 2035 to meet the government’s desired RE capacity share targets in those years.

Untapped hydropower resources

The bulk of Malaysia’s untapped hydropower resources is in Sarawak. They will be developed according to the State’s long-term plans to meet its promotions to attract energy-intensive industries for the State’s economic growth and jobs creation.

As shown in the above charts, hydropower forms Malaysia’s largest RE development share.

Solar PV capacity is undoubtedly being developed as rapidly as planned and desired, albeit with slight hurdles in achieving their original CODs (Commercial Operating Dates). Still, other RE resources do not appear to enjoy the same success.

The multiple mechanisms that promote solar PV capacity additions, such as rooftop installations, NEM (Net Energy Metering), SelfCo (Self consumption), and PV Farms and the LSS/USS (Large Scale Solar/Utility Scale Solar) can meet its capacity growth targets over the period covered by the MyRER, 2035.

Malaysia is reported to “have abundant biomass waste”, especially from the oil palm plantations and the forest/timber industry. Unfortunately, this sentiment seems to forget that a substantial portion of that “biomass waste” is an essential commodity used as an agricultural input or energy source in those industries.

The remaining surplus waste is generally scattered and not easily consolidated as economically viable waste for electricity-generating power plants. Consolidating (or clustering as MyRER has termed and recommended it) also faces the commodity (waste) cost and transport logistics element, making such options somewhat unrealistic.

However, the indicated development of geothermal electricity generation, even by 2035, is perhaps an unlikely option. The forecast 30 MW of geothermal capacity has been abandoned, as shown in the excerpts below.

In a way, this report brings to mind the memory of the Desertec Industrial Initiative (DII), Nevertheless, Malaysia can still confidently look forward to attaining its RE generation capacity share targets for 2035.

Does this mean Malaysia can comfortably achieve its Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2050 target?

There appears to be no specific policy document defining how the NZE target will be achieved. Still, the current pace of emission reduction initiatives certainly needs to be substantially enhanced for Malaysia to do so.